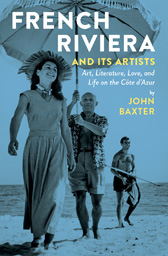

Author John Baxter presents another fascinating story to add to his latest Museyon title French Riviera and Its Artists: Art, Literature, Love, and Life on the Côte d’Azur. Enjoy this special promotional chapter about the photographer Jacques-Henri Lartigue!

In 1962, a placid white-haired Frenchman of sixty-nine wandered into the Manhattan offices of photography agent Charles Rado. With him was a much younger woman, dark-haired and dramatic. Between them, they carried a bulky album full of photographs.The man was Jacques-Henri Lartigue; the woman his third wife, Florette. She explained that her husband, a lifelong amateur photographer, wished to offer some of his early images for sale.

Without expecting much, Rado opened the album—and gaped as turn-of-the twentieth-century Paris leaped out at him. He’d expected photographs of the 1920s and 1930s. Instead, he saw ladies in plumed hats strolling with their tiny Pekinese and Jack Russells. All were dressed in the height of a fashion that disappeared before World War I.

Rado turned the album pages in increasing disbelief. Here were aircraft as fragile as kites wheeling in empty skies, primitive racing cars cornering on unpaved country roads; a girl in Edwardian dress frozen in the instant of leaping down a flight of stairs—and each image preserving that crucial sliver of time that the famous French photographer, Henri Cartier-Bresson, defined as “the decisive moment.”

Some of the photographs were even in color. Rado recognized the soft pastels of the cumbersome Autochrome Lumiére process, which hadn’t been used since the 1920s.

“My first wife, Bibi,” Lartigue explained, pointing to a color photograph of a woman in a cloche hat sitting at a sunlit seaside restaurant. “That was taken in the Hotel du Cap Eden-Roc at Cap d’Antibes in 1920.”

Next to each image, a neatly written annotation gave its date and location, as well as personal notes—on the circumstances of the picture or Lartigue’s state of mind when he took it: a diary in both words and pictures.

“But why have I never seen these before?” asked Rado. “Where were they published?”

“Oh, I never took photographs as a profession,” said Lartigue. “I made these for my own pleasure.”

Bit by bit, Lartigue’s story emerged. He was born in 1894 into a life of wealth and privilege. His father was France’s eighth richest man—and a keen amateur photographer. He gave his son his first camera when he was eight, and taught him how to use it.

By today’s standards, cameras of the time were primitive. Automatic exposures were unknown. One had to judge the amount of light needed and the speed of the shutter required to freeze the action. Right from the start, however, Lartigue’s eye was unerring. He delighted in catching his cousin Bichonnade in mid-leap; a diver at the instant before he hit the water; a tennis player as she bounded after a ball.

The first entry in his journal, dated 1902, read “Suppose I go to the park to photograph the ladies in the most outrageous and beautiful hats?” The eight year old headed for the Bois de Boulogne, the wooded park on the edge of Paris where the rich and fashionable strolled or rode each afternoon. Nobody questioned his right to photograph them. In his expensive clothes and carrying a state-of-the-art camera, the little boy was obviously One Of Them.

He continued taking photos for half a century. People got used to Jacques-Henri’s camera and indulged his hobby. The leaping tennis player in his photograph was no amateur but the French champion Suzanne Lenglen. The pretty girls in summer dresses were socialites and fashion models, and the beaches where they lounged were at Deauville, Antibes and Cannes. His subjects included his first wife, Madeleine, called Bibi, who was herself a celebrity, the daughter of composer André Messager.

Leafing through the album, Rado’s eye was caught by other images of a slim dark-eyed girl who stared out boldly, slouching in beach pajamas that could only have been designed by Schiaparelli or Poiret. Long-faced, dark and solemn, she might have stepped from a canvas by Modigliani.

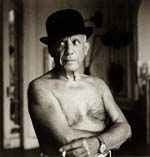

“My friend Renée Perle,” explained Lartigue. “And see, here is Pablo Picasso.”

Rado blinked at an image of the scowling painter, bare-chested but wearing a bowler hat. It could have been taken yesterday.

“When did you stop taking photographs?”

“Oh, I never did. The Picasso pictures are quite recent.” He pointed to his notation. “You see, 1955. Antibes.”

“Then how many more albums like this are there?”

“Oh, a hundred, at least. And thousands of other images. Glass plates too. I’ve never counted.”

Favored by good fortune most of his life, Lartigue was lucky again in going to Rado when he did. The agent showed his photographs to John Szarkowski, the newly appointed Director of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art. Szarkowski believed that photography had become too formal and remote. The future belonged to those who captured their subjects on the run and recorded life in all its unposed disorder. In the catalog for the exhibition of Lartigue’s images staged at the museum the following year, Szarkowski proposed him as “the precursor of all that is lively and interesting in the middle of the twentieth century.”

But Jacques-Henri disagreed. “I am not part of history,” he said. “Basically I am extremely self-centered and selfish. I only take notice of what interests me or amuses me.” Above all, that was women. From his first images of his nanny Dudu and his cousins, taken in the garden of their house in the leafy suburbs of Paris, they were his lifetime preoccupation.

“Nothing hinders my eyes from roaming, drifting endlessly,” he wrote of his days strolling the esplanades of both the Channel and Mediterranean Rivieras. He noticed what women wore; how they did their hair; what make-up they used. He saw how straw-soled espadrilles became the new fashion, so women discarded stockings to go bare-legged. Hats too disappeared. Nor was it any longer declassée to be tanned.Fingernails fascinated Lartigue to the point of fetishism. To please him, his wives and mistresses had their nails manicured in his preferred almond shape, and lacquered in exotic colors. Even the timid Bibi did so, though she was too shy to expose her pink-varnished nails in public, and so always wore gloves.

Nudes didn’t interest him. Even snapping Bibi taking a bath, he showed nothing that would not be seen in a studio portrait. He was more drawn to women dressed and made-up in the height of fashion.

Lartigue’s privileged life ended abruptly with the stock market crash of 1929. Forced for the first time to earn a living, he never considered exploiting his photographic skill. Instead he became a portrait painter. He compromised his amateurism only once. When he heard in 1933 that a modern-dress film was being made of Pierre Louys’ erotic satire The Adventures of King Pausole, about a monarch with a wife for each night of the year, he became its stills photographer, producing a sensual photo essay of showgirls in shorts and t-shirts lounging by the dozens in the Riviera sun.

In 1930, he met statuesque fashion model Renée Perle. His diary recorded his excitement as he waited for a rendezvous.Paris, March 7, 1930: Five thirty-five. There she is! Can it really be her? Ravishing, tall, slim, with a small mouth and full lips, and dark porcelain eyes. She casts aside her fur coat in a gust of warm perfume. We’re going to dance. Mexican? Cuban? Her very small head sits on a very long neck. She is tall; her mouth is at the level of my chin. When we dance, my mouth is not far from her mouth. Her hair brushes against both. Delicious.

She takes off her gloves. Long, little girl’s hands. Something in my mind starts dancing at the thought that one day perhaps she would agree to paint the nails of those hands…

During their two years together, Jacques-Henri photographed Renée hundreds of times, most often on the Riviera. Her willowy body suited the languid, almost tropical vegetation of the south while her dark complexion glowed against the white walls of Mediterranean architecture.

Between the revelation of the 1963 MoMA show and his death in 1986, Lartigue was never out of the limelight. In 1974, President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing commissioned him to shoot his official portrait. But while he basked in his fame as he had in the sunlight of the Côte d’Azur, Lartigue remained an enigma. Critics refused to believe that such images—“probing, observant, sophisticated, and mocking”—could have been produced by someone interested only in having a good time. In reality, he was, they suggested, “out to prove his insider knowledge—to show he knew what was in fashion, that he noticed how people scrutinized each other, that he understood the humor of personal vanity.”

Lartigue just smiled his little cat smile and shook his head. “There is a spectator in me who watches,” he said, “with no concern for specific events, without knowing if what is happening is serious, sad, important, funny or not. Happily, I am an amateur, I do nothing but what amuses me.” (He may, someone remarked, be the only twentieth-century artist to be famous for his happiness.)

So what advice would he give to an aspiring photographer?

The old man shrugged. Surely the answer was obvious.

“To fall in love.”

French Riviera and Its Artists: Art, Literature, Love, and Life on the Côte d’Azur

MUSEYON BOOKS Smart City Guides for Travel, History, Art and Film Lovers

MUSEYON BOOKS Smart City Guides for Travel, History, Art and Film Lovers